Anyone who knows me enough to talk to me knows I’ve been obnoxiously in love with my garden over the last two years. “What have you been doing lately?” followed by “Let me tell you about my garden.” Maybe this is because I’ve always wanted to be the kind of person who raised and preserved her own food like my parents had or my friend Kim who makes it look easy. But it’s hard work so I’ve failed gardening miserably in the past, ambitiously planting but not keeping up with the weeds. It has taken me years to construct a system that works for me. One that doesn’t overwhelm me when crabgrass takes over. I’ve landed on a series of raised beds that I can tackle one at a time. Flowers here, vegetables there. Some perennials, some annuals. An aesthetically pleasing array, and, oh, the birds! My Merlin Bird Identifier registers 10-15 birds’ songs every morning. We have regular families of Mockingbirds, Cardinals, Redwing Blackbirds, Doves, Indigo Buntings, Flickers, Warblers, Finches, Wrens, Robins, and of course Crows and more. You name it, ours is rich with variety too many to name properly. I’ve even seen a Boston Oriole and a Yellow Billed Cuckoo! Working with the earth and nature spirits has been my saving grace. Something I can put my hard work and love into and reap the benefits. People will disappoint. Nature rarely does.

After building the raised beds, we hung cattle panel fencing around the garden with gates on three sides. I was so proud of my design I wanted to decorate it with more than flowers. I attached metal art panels on each of the gates and placed a gazing ball in the middle of my herbs, I hung a small metal birdhouse in the shape of an owl’s head with a small round opening for a mouth. A cruel joke but so very cute. From the top of its head was a dainty little chain and hook so I hooked this over a nail at the corner gatepost so I could see it from the house. I truly thought of this little owl as ornamental and not as a real bird house at all, or else I would have attached it with more vigor. Yet, all summer I have enjoyed watching a pair of Eastern Bluebirds return to this box time and again, climbing in and out of the owl’s mouth with dried grass from our compost or food for their babies. The box is eye level so I can sneak a peak each time I enter the garden.

From my usual spot on the back porch where I sit in the mornings with tea and a journal, or in the gloaming of day’s end, the garden with its little family of bluebirds is in my natural gaze. Behind them, a stand of cosmos. Beside me, a pair of binoculars. From my seat to the garden gate is approximately 50 feet. There is a boxelder tree between us that gives shade to the yard and holds a hammock. The garden gets full morning sun and then the tree protects that little metal birdhouse on the corner from getting too hot in the late afternoon. The first time I saw the birds furnishing their nest, I was a child again, only now I didn’t have to tiptoe or have my dad hold me up to see inside. Before long I was counting eggs, waiting for them to hatch. I watched each day as the couple took turns being in the box or keeping watch on the fence adjacent to it. Once I saw Papa fight off a larger bird that came too close. One evening when Mama and Papa bird must have been on a date or on a run to the grocery, I absentmindedly went to work in the garden without peaking at our babies and they squawked at me with their mouths wide open. If I’d had a worm, freshly chewed, I’d have dropped it in their eager beaks for sure. I felt like their nanny. I anticipated seeing them fledge any day and watched them closely so I could monitor my dogs’ activities and keep the little bundles of joy safe as they shored up their confidence. But the next afternoon, they were gone.

My first thought was not the grave one. Had they fledged during the night? Had I missed the flight while I was at work? Were my bluebirds so gifted at flying that they didn’t need practice? They were perfect, after all. Of course, I did land on the idea that something terrible had happened, after I went inside my garden fence to find a smattering of downy feathers peppering my beans.

The parents wasted no time cleaning out the box. Before long they were remodeling with new tufts of straw. I admired their tenacity. Maybe that’s how they grieve. I remember keeping myself busy when experiencing my own empty nest for the first time. And this gardening surge came along at a time when I needed the earth’s grounding and something to look forward to. Again, I watched their progress, counted their eggs and waited. In the meantime, I googled natural enemies and predators of the eastern bluebird. I found all kinds of ideas for protecting the box from predators.

We live in a healthy ecosystem on our farm by the river. We readily hear and see hawks, owls. We even had an eagle land in our yard once, but he was eating a groundhog. Too big for that little birdhouse. Rabbits are everywhere this year. I imagine that’s keeping the pack of coyotes happy who we mostly hear at night, down by the river. We watch parades of deer and turkey daily. We occasionally smell a skunk who’s perfume wafts in an open window at night and signals the dogs to bark. The peepers in the barn lot pond are deafening at times, especially if it’s going to rain. When I run the soaker hose in the tomatoes, I almost always see a fat bullfrog enjoying the puddles left from a leaky faucet.

I know there is death on the farm, I’ve witnessed it. Coyotes having Thanksgiving Turkey, Bobcats catching rabbits. Mockingbirds stalking and desecrating Luna Moths—which I find especially egregious. Sometimes the beauty and wonder of nature is so brutal it can break your heart wide open. What I haven’t mentioned is obvious. Google says the snake is #1 on the list of suspects. All of the friends to whom I’ve mentioned my bluebirds say, “Snake.” I say “I don’t think so.” Here’s why:

- That smattering of feathers left behind. Another bird or a racoon would leave feathers behind but maybe a snake would swallow whole?

- We mow about an acre all the way around our house and garden. We and/or the dogs are actively in the yard every day; claiming our territory.

- The bullfrogs haven’t been snatched yet.

- Most Important** and this is the kicker: I made a pact with their leader, a 6-plus foot black rat snake that I found on my porch one night (that’s another story) just after I moved in. I told her we had 140 acres here and if she would spread the word among her kind that I live in the house and the mowed part of the yard, they could choose their territories over the rest of the farm. The house had been sitting empty a few months. Maybe she had been delegated to check out the new neighbor. I requested she take the barn lot closest to the house to keep the poisonous snakes farther away. A rumor I’d heard but she said nothing, although she did as I’d suggested. She already understood the benefits of that location. I leave them alone. They leave me alone. We’re all happy.

This has been a good partnership for 12 years now. We sometimes see a random snake in a field, near the barn or on the road but for the most part not close enough to the house to have a reminder talk with them. I’ve only broken my end of the bargain once, last year, when I wanted an old wagon wheel for my herb garden. It was lying in a pile of antique farm equipment I call “the boneyard”. Several wheels and other pieces of antique mule driven farm equipment had been abandoned in the barn lot and overgrown in upstart trees, shrubs and tangles of honeysuckle since my dad traded his mules for a tractor in the early 70’s. It looks like where the 19th century went to die. I’ve seen my snake friend and her family there many times, on my walks. It’s the perfect location between a barn full of mice and a pond for frogs and drinking water. I knew I’d have to breech my contract with her but I hoped to be in and out without notice. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still scared of snakes. I don’t want to see one, and especially not be close enough to touch it, although I will give a snake a good talking to if I do see it. I’ve always known she was there and I’ve left her alone. I asked my companion to help me recover the easiest wheel I’d spotted and we donned our knee-high boots and work gloves and hiked over. As he pulled and cut and sawed through tough vines, I talked to her and apologized for coming into her home. I hoped she would forgive me. Turns out, she was wrapped around the very wheel we were pulling on. She disappeared quickly into the brush and we both jumped. I continued apologizing, profusely. I looked like a child hopping on one foot and then another while flicking my hands to shoo her away. I wondered then about payback but soon forgot as the spokes of the wagon wheel—lying flat on the ground—made a great dividing frame for my sage, rosemary, thyme and oregano.

My little bluebirds continued to teach me about persistence, making 2 more nests in a row. Again, I watched, counted, waited. Nothing. No more feathers were found but neither did I witness hatchlings learning to fly. The evidence was mounting but I hoped and decided that without seeing feathers, I’d simply missed their flights while at work. Three times! I was happy and surprised when the birds came back for a fourth time, cleaning, re-stocking, preparing.

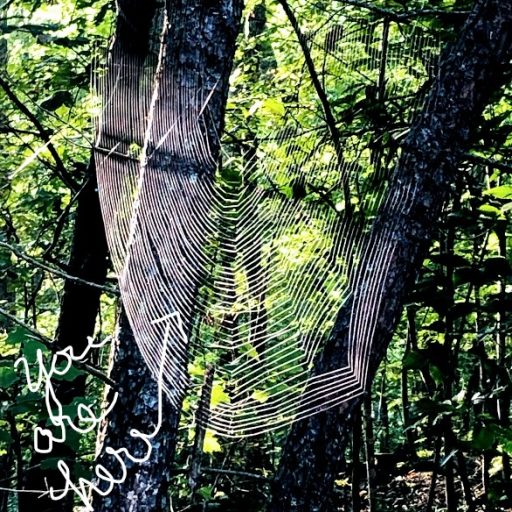

A few days ago, I went out to enjoy the sounds of morning bird frenzy, as usual to collect a few minutes on a cool porch before the heat set in. Our days have been scorchers lately. To my surprise, dangling from the lowest tree limb of my backyard box elder, within ten feet and direct eyeshot of the owl’s open mouth, was the shed skin of a snake, about 3 feet long! Too bad the owl isn’t real. The skin did not belong to my friend the reptilian Queen, who I’d put in charge, because she is much longer than this interloper. One of her not so loyal subjects had snuck into forbidden territory!

As I sat, contemplating how to renegotiate peace talks, my partner told me he’d found a baby copperhead enjoying the heat of the compost pile about a month back. Although he’d killed the one he’d found I realized chaos had ensued without my knowledge!

“A baby?” I asked, “Only one? Are you sure there weren’t more?” Youngsters can go rogue without yet knowing the unwritten rules of their elders. That’s understandable. But as every old person says, this younger generation has a different set of values. Leaving the skin in both my view and that of the birdhouse, is a blatant show of disrespect. Also, I was aware this was supposed to be the year of the cicada invasion. Although our region hasn’t been the hardest hit, for months now, Rosie and Willow—otherwise known as dog patrol or affectionately “the girls”—have been staying out late to dig for beetles or cicadas or whatever other little crunchy larvae might be there. I’d read an article about snakes gathering beneath oak trees at night to eat the emerging cicadas and I hoped my girls were abating that possibility.

I wasn’t sure if Queen Rat Snake was dead, if there had been a coup for leadership, or perhaps she felt I owed her one after my breech into her territory last year. Maybe she decided staying out of my yard in a cicada year was too much for me to ask.

I went back to writing in my journal, listening to the usual morning rush of cardinals, jays and mockingbirds as they come into the garden for breakfast when I heard a flush of excitement. The bluebirds were back. They had spotted the skin and were sounding all the alarms. Mama was flapping her wings hard, hovering in front of the scaly replica, and if I had to guess cursing him mightily. I hoped she didn’t have a heart attack. I could almost feel how the realization hit her. Grieving her babies while finally getting closure for where they went. This brought Papa. They flew above it, below it, hovered in front of it, flapping their wings and yelling as if to scare it away. It didn’t budge, of course, except for wavering in the wind. The birds called in the cavalry and here came the flickers and mockingbirds, a larger line of defense. They too used their best scare tactics and sounded alarms which pulled in the officers—cardinals and jays. With all the sirens going off, it was the only show to watch, even the dogs were captivated. We were the rubberneckers at the scene of a crime; all traffic stopped. It seemed the teams had forgotten their colors and all acted as one unit to rid the area of this menace. They did all share the same feeders, after all. When the decomposing skin did not respond to their fury, except to sway with the breeze, they finally lost interest and gave it up for dead.

The skin still hangs as a reminder. My hammock chair also hangs in that tree. It’s the only tree I’ve got whose limbs are hammock or swing friendly. I’m not sure how long it will take me to sit there again, unsure what might be overhead. I know the bluebirds have not returned to their box. As with all trauma, it’s gonna take time. Well played Queen. I won’t be taking you for granted again.